The legal report on the Don Pepe apartmentsapartments, which is in the possession of La Voz de Ibizadoes not introduce a concept alien to Spanish law. On the contrary: it is based on a principle fully recognized by the legal system: the presumption of legality .

Thus, it argues that the current absence of an administrative document cannot automatically become an illegality imputable to the citizen. Understanding what this principle actually means – and what it does not – is key to understanding the legal twist that the opinion puts forward.

The presumption of legality is in the law.

In Spanish administrative law, the presumption of legality has a clear and express formulation.

Article 39.1 of Law 39/2015, on Common Administrative Procedure, states that, “The acts of the Public Administrations subject to Administrative Law shall be presumed valid and shall produce effects from the date on which they are issued.”

This means that all administrative acts are presumed to be in accordance with the law until they are annulled through legal channels.

-

The next step to reverse the Don Pepe’s declaration of ruin

-

Don Pepe: the independent report states that it is “technically and constructively rehabitable”.

This presumption is not decorative: it shifts the burden of proof to the challenger, guarantees legal certainty and protects the legitimate expectations of citizens with respect to public actions.

The key nuance: when the act does not appear

The Don Pepe case does not fit exactly in the “classic” assumption of Article 39, because the administrative document of the Block A license is not preserved.

And here is the fine -and legally relevant- point of the report. It is that the law does not remain mute when the document is missing, much less does it automatically convert that absence into an illegality.

With this, case law has developed a presumption of material legality or by appearance, based on the existence of a real processing, the absence of an express denial, the subsequent conduct of the Administration and the impossibility for the Administration to benefit from its own error, inactivity or loss of documents.

What the jurisprudence says

The report cites rulings of the Supreme Court and the Constitutional Court that develop a constant idea: the Administration may not use its own non-compliance to harm the administered party.

Among others, resolutions are cited that establish that administrative silence is for the benefit of the citizen and that it is not lawful for the Administration to take advantage of the fact that it has not resolved or documented, nor to convert its passivity into a deferred sanction decades later.

How does the report apply this presumption to the Don Pepe case?

The opinion does not state that a non-existent license “appears”. What it does is to legally reconstruct the record on the basis of established facts.

-

Countdown for the Don Pepe: neighbors’ assembly convened and expectations are high

-

Neighbors barricaded in Don Pepe: “Let everyone see how the houses are after so many years”.

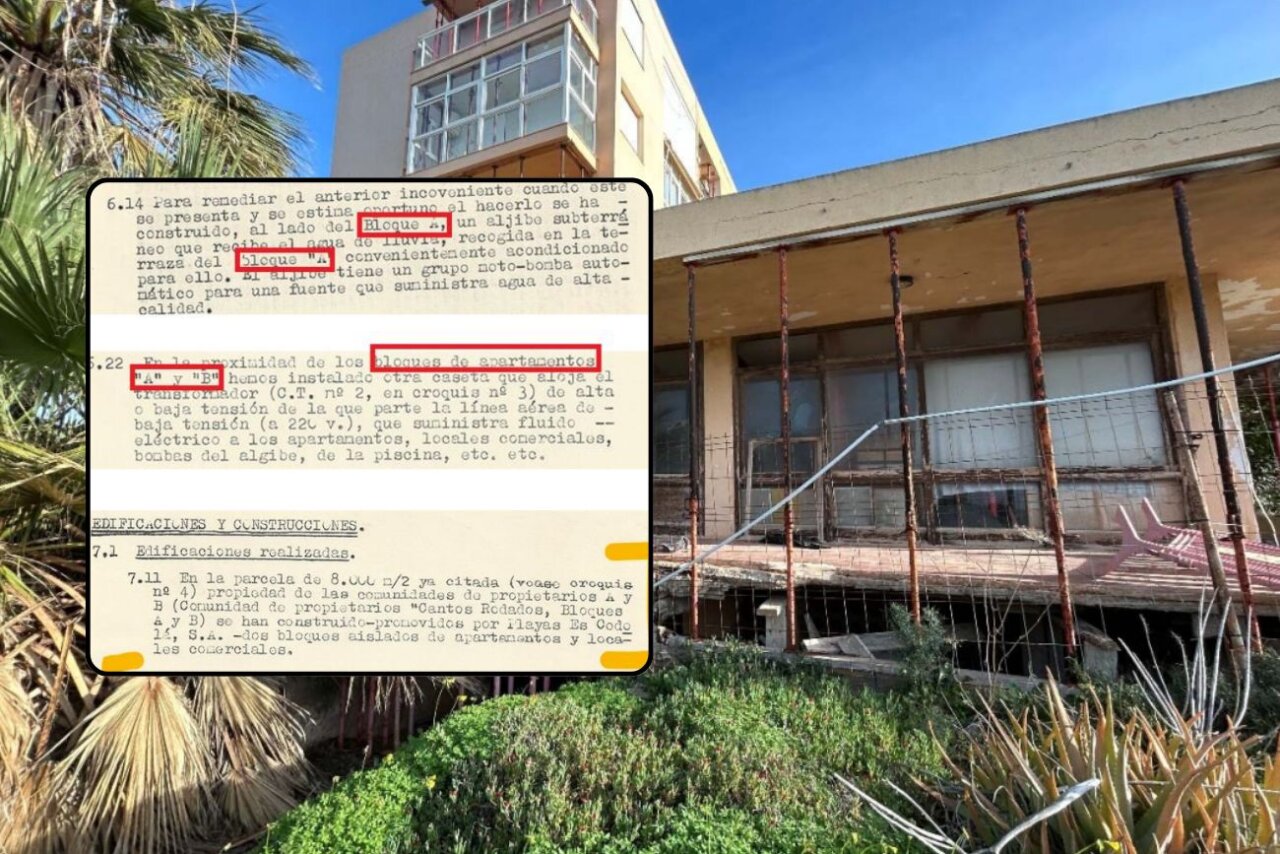

In 1964, two applications and two approved projects were submitted for two identical blocks. However, only the license for block B is retained, although there is no record of refusal for block A.

In addition, the License Register book for that period is missing.

On the other hand, there are subsequent acts consistent with legality: military authorization for two buildings, deeds that speak of administrative authorizations, horizontal division and planning that incorporates both blocks.

Based on this set, the report argues that there is sufficient evidence for a presumption of legality of Block A, or, to put it more precisely, that it cannot be treated as a clandestine construction just because no paper appears today.

Neither licensed nor legal

Anyway, the presumption of legality does not mean granting a retroactive license today, nor does it mean that everything built is automatically legal.

The report itself warns of extensions, changes of use and subsequent unprotected works, which inevitably leads to the debate on the out-of-order status.

The presumption of legality does not erase the problem, but it prevents the entire building from being condemned by a historic administrative failure.

If this legal approach is accepted, the Don Pepe case ceases to revolve around a binary question (is there a license or not?) and moves on to a much more relevant one: what urban planning regime corresponds today to a building whose origin cannot be treated as illegal by default?

Continue reading:

-

Don Pepe neighbors’ hope: one more step to reverse the declaration of ruin of block A

-

Don Pepe: “If everything goes well, it will allow us to get out of this nightmare”.

-

Don Pepe: a technician will assess the possibility of lifting the declaration of ruin

-

Govern, Consell and Sant Josep seek legal ways for the return of families to Don Pepe

-

PSOE accuses the Government of “deceiving” the families of the Don Pepe with unfulfilled promises