“Is it possible to dedicate an article?”, asks Martín Monroy(Montevideo, Uruguay, 1989), after the interview that follows but before its publication in this medium. The unpublished question has a heartfelt reason: he explains that after the talk with La Voz de Ibiza, he learned of the death of Uruguayan footballer Juan Izquierdo. Monroy is deeply sorry for the death of his colleague. The world is also in shock: the athlete was 27 years old and suffered a heart attack that took everyone by surprise during a Copa Libertadores match.

So, at his request, these humble lines are in memory of Juan Izquierdo.

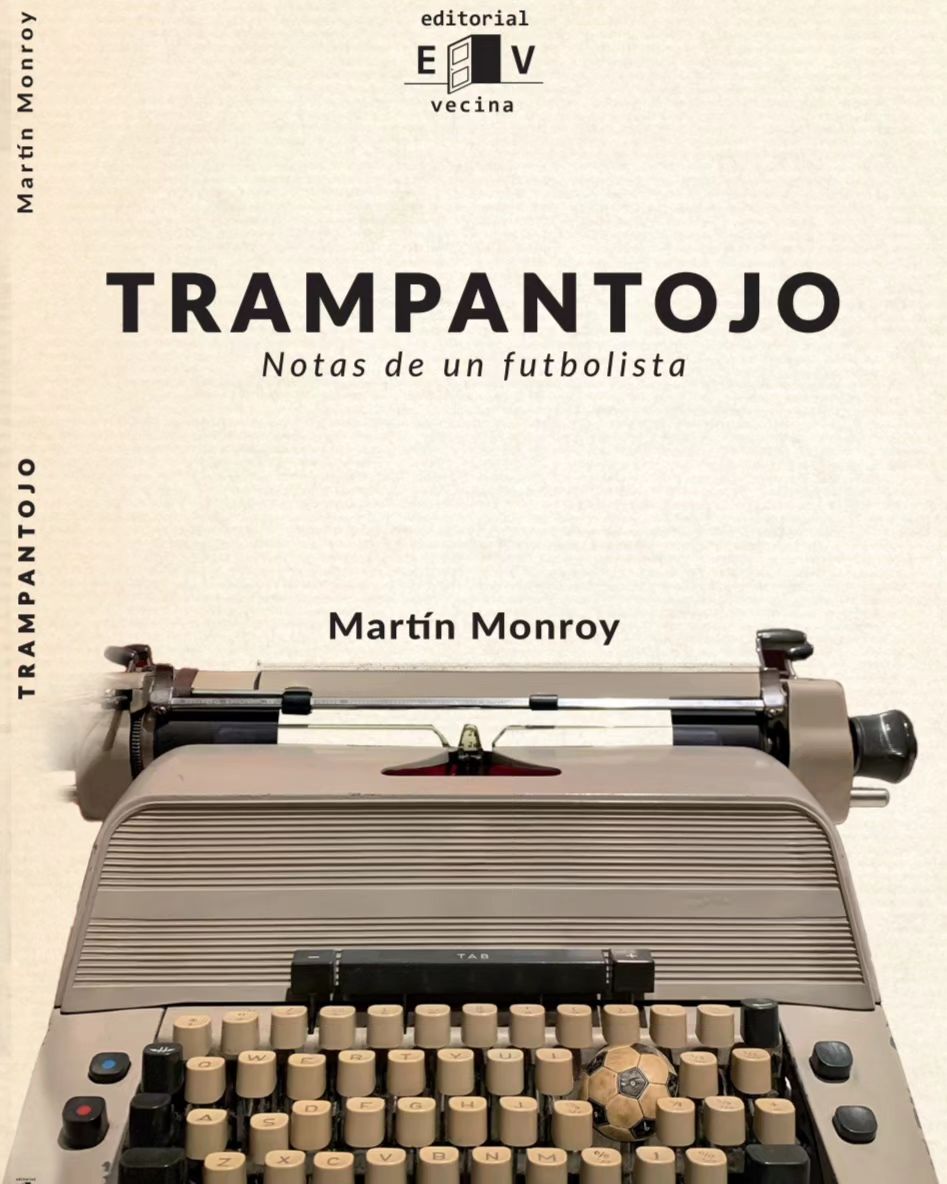

The talk with Monroy is for the publication and presentation of his first book, Trampantojo, notes of a soccer player (Editorial Vecina). The presentation was yesterday in Es jardí, Sa Caleta, weeks after he presented it in his homeland.

It is necessary to review the steps that led him from the soccer fields to turn to writing. A native of Montevideo, he grew up with the aroma and rhythm of the port internalized: his father was a sailor. Today, the sea, its only scent of salt, gives him calm. Perhaps that is partly why he chooses, at this moment, to make the island of Ibiza his home: “It takes me back to my childhood”.

Monroy has been involved in soccer since he was a child. He remembers going to school, training, returning tired to sleep and starting all over again. In Uruguay he played in La Escalinata, River, youth in Deportivo Uruguay, debuted in first team in Rentistas, Sud América. He went to play in Brazil (where he was deceived with the contract, he was promised double what he was finally paid and thus he knew the “betrayal”), returned to Uruguay and Sud America, Rocha, Albion. He started working in a bookstore while playing for Basáñez and finally left professional soccer. He lived in Madrid as sporting director of Aula, but, before that, Ibiza: he played in Sant Jordi and Sant Josep.

“Soccer led me to live in other countries, to play soccer and earn money for it, to be a professional, to be a profession, to train every day. It also made my body ache a lot, to have to hide some injuries because you have to play on weekends, that this is your economic income but to deal with the uncertainty when a contract is ending or when you are just starting, to what it is to be a foreigner, to have all eyes on you because you have to perform, the competitiveness… and to see a lot of friends and teammates who were left along the way and how their lives were torn apart”, he expresses, curiously just before the news of the death of his compatriot circulates.

-There is little talk about what we could call the “B side” of a soccer player’s life, isn’t there?

-Yes, it’s a profession in which you are shaped. From the age of 13 you are competing and you miss out on a lot of things from your youth. You compete at a certain level that becomes harder and harder if you want to be a professional. At times you share with the best and you can’t fail. You know that if you fail, you’re out. Or if you had no press. Besides, I don’t like lightness, and lightness leads to a show, bread and circuses. But a lot of things happen in soccer, not only what is on TV. Sometimes you don’t get paid for a month. Or you can’t commit yourself too much to certain issues in life because six months later you’re moving again. And there are few people who make guita (money).

“It’s a job you do every day and with your body. You think you take care of it and it’s not like that. My left knee was already broken. I had thought about stopping playing even as an amateur, my body already hurt a lot. But there is something in the game that touches me and that cannot be satisfied… training, shooting, definition, that goes where I want it to go. Those things touch me something that I associate with joy. Finally, I finished breaking my knee and now I have to wear a knee brace to walk, I have surgery next month. I’m on leave from the club in Madrid where I was working,” he adds.

Martín Monroy, Ibiza, soccer and writing

If soccer opened the door to Ibiza, Ibiza opened the door for him to develop as a writer.

Although there was already a seed planted in him. He remembers writing some texts as a child: “There was something in soccer that was not enough for me. There was a place I wanted to get to, but I couldn’t get there with soccer.

He published in some sports portals when he was in Uruguay. Then, something else sparked when he heard Agustín Lucas, another Uruguayan soccer player, also a poet, recite his poem La Pasionaria after Sud América won the B championship in 2013 and went to first division. “The poem talks about the soccer player, and says something like ‘poor, powerful, poor for sale, we are mediocre even if they lie to us,'” Martín says.

In the age of social networks, he shared some of his writings on Facebook and Instagram. And one day, playing in Ibiza, he went one night to see La Vela Puerca, an Uruguayan band, play at Las Dalias. The journalist Manu Gon, with whom he was already connected in the virtual world, read his text and suggested and proposed it to be published in the Periódico de Ibiza. There he met Agustí Sintes Vallés, who was director, today director and founder of La Voz de Ibiza and who proposed him to continue writing with a regular column.

“I was already looking for other ways of life, looking to travel other paths. Now I understand that I was also looking to escape a little. I needed to go through certain processes that would be useful for my development as a human being,” he reflects.

‘Trompe l’oeil, notes from a soccer player’.

-There is a prejudice that makes it difficult to think of soccer players as writers as well. Do you agree?

-Yes, I live with that prejudice.

-And what is this coexistence like?

-At the moment, very good. But a certain amount of time has to pass. Like when you are a player: certain matches have to pass for the fans to get to know you, to trust you, for you to give them joy. No matter how you perform that weekend, you know that there is something else. Something like that happened to me with writing. I had to break with a certain life, with being defined as “the kid who plays soccer” since I was a child. Then, it becomes part of your life and gives you something that nothing else gives you. At that moment, you don’t give a shit about anything and you don’t care what anyone says.

I do care about friendship. I was lucky enough, and this will stay with me forever, to have made my first book with a brother in my life. A great friend, named Sabrina, designed the cover and did the illustrations inside. Juan Francisco Bo wrote the prologue. Paty Pujol, a journalist friend that I adore and admire wrote the back cover. In the end, it is always a team effort.

-How did “Trompe l’oeil” begin to take shape as a book?

-Last year, a friend of mine, Maxi Castilla, also a soccer player and a writer, invited me to a project. A cardboard publishing house was proposing to publish stories written by soccer players. There were five of us in total. I like to do things well and I started a workshop with Agustín Lucas to prepare those texts. At one point, we realized that there was something else, between my notes and everything. That’s how it came about.

-Why the title? I must confess that I did not know the word….

-First, that’s why. A word that many people don’t know. On the other hand, I like to listen to La Venganza será terrible every morning (a radio program by Argentineans Alejandro Dolina, Patricio Barton and Gillespi). It is a humor that amuses me a lot and accompanies me every morning, and that also raises questions and opens creative portals for me. One day, Dolina started talking about the concept of trompe l’oeil and also about Coleridge saying that, without illusion, soccer is useless. I looked up what it meant and discovered that it was a style of painting that sought to deceive the human eye. I kept that idea, that of something illusory. I wrote the word down on a piece of paper and forgot about it. Once the book was underway, I found that note again and I knew it was the title I was missing.

-How much fiction and how much reality is there in what you tell in the book?

-Everything and nothing.

Monroy plans to continue his days in the Ibiza that invited him to give shape to that “something more” he was looking for: “Here I have many people that I love and love me. I have the feeling that I can form a home, a place to share and also to be in solitude, especially because I have another book in mind that I want to face”.