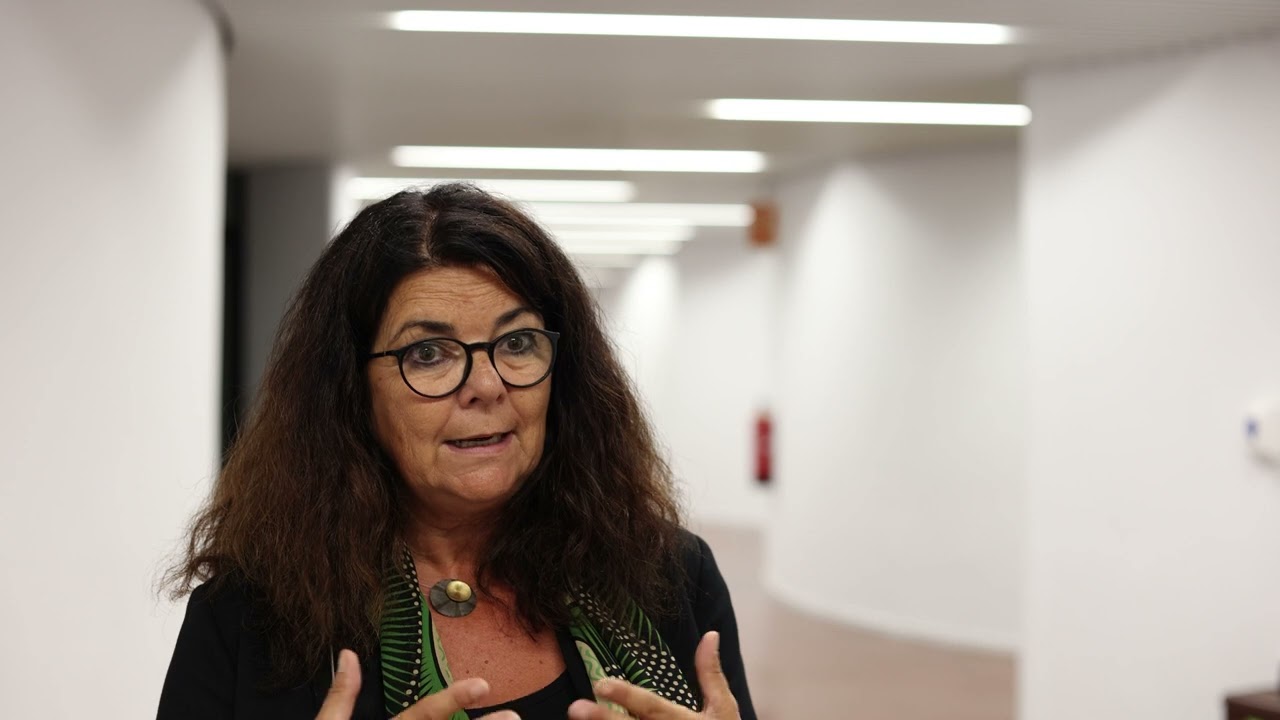

The housing crisis that Ibiza and the Balearic Islands as a whole are going through requires expert views beyond the short term and the immediate political debate. One of them is that of Montserrat Pareja-Eastaway, PhD in Economics and president of the European Network for Housing Research (ENHR), one of the main international academic networks dedicated to the study of housing markets and public policies in Europe.

A reference in urban and residential analysis, Pareja-Eastaway, who lives between Barcelona and Menorca, provides a structural vision of the causes of rising prices, the difficulties of access and the limits of the solutions that are being proposed in particularly stressed areas such as Ibiza.

Montserrat Pareja-Eastaway, in addition to being a full professor at the University of Barcelona and a researcher in housing and urban economics, with an academic and professional career involved in housing issues as an element of social cohesion, also chairs the European Network for Housing Research (ENHR), an international non-profit academic network founded in 1988 that brings together researchers, academics and experts in housing and urban policies from all over Europe and other countries.

The entity acts as a reference space for the analysis of residential markets, housing access and affordability, renting, social housing and the phenomena of residential inequality, gentrification and sustainability.

Through international conferences, thematic working groups and collaboration between universities and research centers, the ENHR serves as a bridge between academic knowledge and the design of public policies on housing.

– How do you rate the housing situation in the Balearic Islands in general and in Ibiza in particular?

– I believe that the situation in the Balearic Islands with respect to housing is very similar to the situation in the rest of Spain and the rest of Europe. The problem of housing affordability is a generalized problem. The housing that is supposed, by Article 47 in the case of the Spanish Constitution, to be a right for citizenship and, at the same time, we know that families are spending a lot of money, more than what would be advisable, which would be 40% of income. Much more is spent in order to have access to housing. A fact from the Balearic Islands is that if we were to look for the number of years of full salary that would be needed to be able to buy a house, it shoots up to 19 years. While, in general, in the rest of the autonomous communities, it stretches around 9 or 10 years. So, really, it is a generalized problem and perhaps, due to a series of circumstances shared by Mallorca, Ibiza and Menorca, the problem is even more serious.

– And are the administrations responding to this seriousness?

– Public responsibility for what would be the right to housing is shared at different levels of government: local, island, state and even today at the European level, since we also have a commissioner and, in principle, a task force, a policy that is going to help, just as the Next Generation funds have done in other aspects. They are going to try to promote this affordability of housing. The institutions have the capacity to regulate, to audit and to make housing plans. The instruments are there. Another thing is that the instruments have been used in an, shall we say, efficient and active way in recent years.

I must say that for the last three years, precisely because of the seriousness of the problem, the institutions have been trying to get down to work. What happens is that, obviously, the ideology is different in the different administrations and, depending a little on the ideology, you are going to opt for one way or another: if the market can solve it or the market cannot solve it and there has to be a greater intervention.

– And what would be the perfect balance between state and market?

– I do not know if the perfect balance exists, I wish it did. But what is true is that, nowadays, the public sector cannot continue to be asked exclusively to take responsibility for tackling the housing problem because, precisely, today it has fewer and fewer budgetary resources. Therefore, given the seriousness of the problem, it is necessary to look for collaborations with other agents. From private developers to non-profit organizations, to neighborhood associations. In other words, it is a matter of seeking much more collaborative solutions, much more shared and with greater strength and credibility. Gaining that trust as real drivers of the solution to the housing problem.

– It calls for a more active role of the private sector.

– Of course, of course. It is a matter of seeking complicities between the private sector and the public sector. And there are instruments to find those complicities. What I will never say is that the private sector should abandon its principles, because that would not make sense. But I would say that, given that housing is a good that shares this duality, that this duality should be reflected by the different actors in the housing system. Be it the public sector, be it the private sector, be it non-profit organizations, be it neighborhood organizations, be it, in short, all those who in some way are linked to the housing system in a given country or context.

Social Housing or Limited Price Housing?

– There is a lot of debate on the issue of subsidized housing vs. affordable housing. Which is the better option?

– For many years, social housing, which is the figure we have in Spain to talk about social housing, has worked and has worked for many reasons for many years. But I believe that now we have to look for more innovative formulas. The limited price is an alternative to what has traditionally been the VPO. But I also believe that there is room to imagine new formulas. Because we are mixing what would be, on the one hand, social housing, which is usually only public rental housing, and affordable housing that can adopt infinite modalities. Something that has been done wrong for many years in our country is that social housing had an expiration date, it ceased to be social housing and went to the free market. This has now been resolved, but somehow we have missed a train. In other countries or in other cities, such as Vienna, for example, they have been able to generate an affordable rental stock for the city, precisely by making it a condition for life for these dwellings to be affordable or to be protected. Well, we have not done this here. So, I do not know if we should continue calling them the same or not, but I think that we have to reformulate in some way how we are considering how to reach social housing. But, I insist, social housing is a problem within the great problem of the lack of affordable housing.

– You talk about more innovative formulas. Which ones?

– They can range from what would be the contribution of public land, with private construction, with management by non-profit entities, depending. In Barcelona, the City Council has been quite brave in the sense of betting on formulas that did not have a tradition or history in the Barcelona context, but in other cities. For example, finding that optimal partnership that favors both the private developer, who is willing to accept a profitability below the market, but a reasonable profitability at the end of the day, with the public sector, which has objectives of preserving what would be the housing rights of citizens, along with non-profit entities, which historically have been those that have managed public housing or non-profit housing, and have a really great expertise. Moreover, as time goes by in Spain as a whole, we see that all the non-profit entities, whether foundations, associations or any other type, are gaining ground, are seeking greater alliances among themselves and trying to generate a certain voice in the sector.

– In Barcelona, for example, it has been declared a tensioned zone. However, the Government argues that it will not apply this figure in the Balearic Islands because it has not solved anything in Barcelona.

– Whether it works or not is not immediately apparent either. And it depends on who you read. Some will say it hasn’t worked at all and others will say it has worked a lot. I think also one of the things we have to start learning is to be innovative in the formulas and experiment. Experimenting is not a bad thing and it is trying to see. When you have such a serious problem as access to housing, try to find solutions, as for example, not only Barcelona or Catalonia have done, but many European cities are doing it, to somehow put limits to the growth of rental prices through the determination of a stressed area. I do not know why it cannot work in Ibiza or in other cities. I still think it is not a long-term solution, far from it. Nor is a long-term solution to build more. Basically what it is about is to look for solutions that somehow palliate the emergency, but also to look for longer term solutions.

– Do you consider it viable to slow down, suspend or somehow limit the construction of free housing with a kind of moratorium, something that is also being discussed here in Ibiza?

– No. Suspending construction does not make sense. What I do believe is that we must be clear about the model of city we want, based on defining certain values and seeking a balance between preserving the environment and also meeting the housing needs of the population. It is not so much a question of prohibiting as of what we want to prioritize. That is what I think is most interesting.

– And why is building more not a solution?

– Because if building more means building high-priced, high-end housing, that is not necessarily going to solve the housing problem, the problem of housing accessibility.

– And is growing taller an option?

– Yes, densification is an element. What happens is that in territories such as the islands it is something that must be done very carefully. I have already been asked this question and I don’t have a clear opinion. Densification in Argentina has one meaning and densification in Norway has another. The same as densifying in the Balearic Islands. I remember once a researcher from Buenos Aires, talking about the problems of densification in Buenos Aires, and at the same time the lady from Oslo said that what we have to do here is to densify because the dispersion is generating an incredible lack of sustainability. Of course, if we consider that the instrument to generate more supply is densification, then it depends if what we want is to become like the countries of Central and Eastern Europe that have generated an infinite number of housing masses, which are not really desirable housing.

What does make a lot of sense is the combination of uses. That is to say, if you have, for example, a school, why can’t you build on top of that school? When I say a school, I mean a kindergarten? That would be the possibility. Densification, of course, has to respect the environment, it cannot distort what would be the very landscape of the islands, which in some cases, see in some areas of Ibiza or Mallorca, and even Menorca, many people think, this should not have been done. It is thinking in the long term.

– What is the responsibility of tourism in this housing crisis?

– It is also one of the big culprits of revenue sources. I understand that it must be part of the human condition, someone has to be to blame, but it is not that. Tourism is an extraordinary source of income. It is the source of income, in many cases. So, demonizing tourism makes no sense, this has also happened in Barcelona. I don’t think that is the solution. It is not the opposition between residents and tourists. Also, many times it is the opposition between residents and immigrants, whatever type they are. Again, it will come back to what I was telling you before, to the principles, to what kind of territory we want. Nowadays, the hotel complexes that sold beach and sun are being questioned and this model is being changed. A bit like in Barcelona: in 2030 it has been foreseen that Airbnb is going to close all its listings. Because the city really considers that there should be no Airbnb when there is such a serious problem of access to housing in the city. Because, indeed, if the human being is reasonable and has an empty house, well, obviously he will go to rent it in the temporary tourist sector, instead of putting it to the private sector. So, that is precisely where the public sector has something to say, something to regulate.

– What measures would you take to improve access to housing?

– Firstly, to encourage public-private partnerships. Second, use urban planning to ensure that new developments also involve the construction of affordable housing. In the short term, why not? What would be the cap, i.e., limiting rents. And, above all, to be clear that housing policy is immersed in a larger policy, which is what kind of city or what kind of territory we want. And, from there, to design infinite instruments, from the purchase of public land. For me, with generalized variations, I believe that public-private collaboration and non-profit, or social, call it what you will, that is the future. And, therefore, any policy or any initiative that supports that, to me, makes perfect sense.

Continue reading:

-

Fewer sales, prices at record highs and more mortgages: this is how October was for housing in the Balearic Islands

-

The price of new housing hits a new record in the Balearic Islands and worsens access to purchase in Ibiza

-

The COAIB warns that 20% of Ibiza’s homes are empty in the midst of a housing crisis

-

Housing, immigration and tourism: Vicent Marí sets Ibiza’s priorities in his Christmas message

-

The Don Pepe negotiation draft and the rehabilitation project: “We are very hopeful”.

-

Fine in Ibiza: renting without a license costs 75% of the value of the home

-

Ibiza starts the process to recover the Isidor Macabich site to be used for ‘coliving’ housing for young people

-

Ibiza consolidates its position as one of the most expensive areas in Spain to buy a luxury home

-

Ibiza and the impossible housing: the desperate plea for a “model” family not to leave the island